Romain Riollet est chercheur en politique environnementale, de science po au CNRS, de Paris à Bruxelles. L'occasion pour nous de rappeler que les scientifiques qui s'expriment dans nos colonnes le font en leur nom propre et nom en celui de leurs organisations.

Il est précisément spécialiste du marché du carbone et

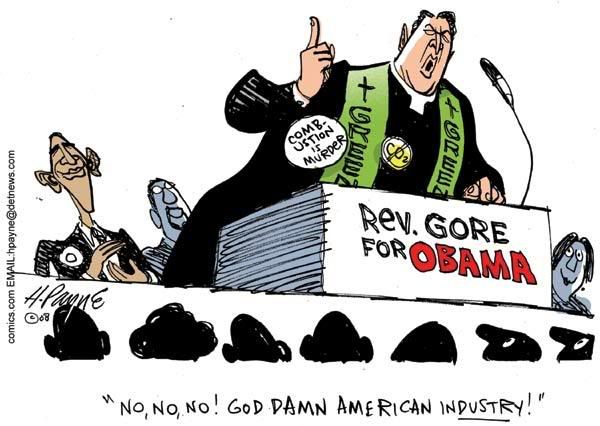

Vous savez la précaution avec laquelle notre media use du crédit scientifique que l’on peut apporter à des engagements politiques (ex. note sur Todd). Pourtant les échéances politiques concernant les défis climatiques mondiaux approchent à grands pas, et il est bien un domaine qui mêle opportunément sciences de la terre et sciences de l’homme, raison pure et raison d’état, alors … Obama va-t-il sauver la planète ?

Obama's (ambiguous) support to next global climate change regime

Barack Obama's election is certainly a political milestone in these troubled times and major expectations have aroused lately.

As a climate policy analyst, however, I must underline with one concrete example that we should remain realistic observers rather than unconditional "obamaniacs".

Still responsible for almost a quarter of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (although China appears to have become the world's largest emitter last year), the US has remained remarkably absent of global climate talks since the Bush administration decided, in March 2001, to leave the Kyoto Protocol negotiation table -despite campaign promises to regulate CO2 emissions. While other developed countries had agreed to binding limits on their GHG emissions, the world's most powerful nation stayed out of the international climate regime and had already increased its emissions 20% over 1990-2005 while others are trying to keep theirs under control.

While the Kyoto Protocol's compliance period started in 2008 and ends in

As many people know, Pdt Obama had pledged American leadership in the field of climate at an early stage and is pushing a strong climate and energy agenda compared with his predecessor. Pdt Obama's election blows a wind of change on international climate negotiations as there now is hardly any doubt that the

While the Nobel Peace prize had been awarded to former US vice-President Al Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (the world's leading authority on climate science) in 2007 "for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change", the only political entity that has devised a climate policy in line with the IPCC's recommandations (limiting climate change to an average

While the US contribution to such a "satisfying agreement" would imply similar emissions reductions in the range of 30% below 1990 levels (some 45% against current levels), Pdt Obama has so far based its climate policy upon the "return to 1990 level" target (15% reduction against current levels)., which was what the US had presented as a "best" possible 2012 commitment more than a decade ago, before it left the Kyoto talks... Not only is his target a blow to US leadership ambitions, it also undevalues the country's massive potential for GHG emission reduction. While energy efficiency, renewables and other clean technology are expected to get substanatial public support in the short term, they could get more efficient economic incentives under a truly ambitious climate policy target -mostly through the pricing of CO2 under a "cap and trade" system similar to that implemented in the EU since 2005.

In short, despite being a major shift from the previous adminsitration, Obama's climate policy remains under ambitious from the perspective of both environmental effectiveness and economic efficiency.

In short, despite being a major shift from the previous adminsitration, Obama's climate policy remains under ambitious from the perspective of both environmental effectiveness and economic efficiency.

But there is worse: having in mind the inertia of international negotiations and the weight the US will have in the current round of climate talks, presenting an outdated climate target (the "return to 1990 levels" was what the US had presented as a "best" possible 2012 commitment 10 years ago, before it left the Kyoto talks) as an element of leadership is likely to greatly reduce the ambition of the international agreement compared to what is scientifically appropriate and cause the failure of international action to contain climate change to a level that will not expose humanity to unmanageable risks.

FACTBOX

IPCC ==> containing Climate Change requires 25-40% GHG emission reduction vs 1990 by 2020 and ≥80% reductions by 2050 from developed countries; developing countries can increase their emissions but should contain that increase 15-30% below 2020 forecast levels.

EU ==> 30% reduction vs

US ==> 1990 levels in 2020 (i.e. 30% short of satisfying target)

developing countries ==> use underambitous US climate policy to reject CO2 constraints in international negotiation

Romain RIOLLET

Merci Romain!